Brad Carr, National Australia Bank’s (NAB) Executive, Digital Governance and Industry Engagement, breaks down the challenges of establishing identity in a digital world, and how public and private sector collaboration will help to enable a secure and interoperable identity ecosystem.

Brad Carr, National Australia Bank’s (NAB) Executive, Digital Governance and Industry Engagement, breaks down the challenges of establishing identity in a digital world, and how public and private sector collaboration will help to enable a secure and interoperable identity ecosystem.

How do you prove who you are on the internet?

And how can you trust the person or entity on the other end?

These are the great challenges of modern digitalised society, with implications for privacy and the security of our data and finances. These arise in everyday scenarios:

- Peer-to-peer transactions and sales on platforms such as eBay and Etsy

- Confirming legitimacy of invoices

- For a business, whether your customer is eligible (eg. meeting an age or residency criterion)

- Recognising qualifications and trade certifications, particularly for migrants

The public and private sector can together solve these challenges — but crucially, neither can do this on their own. An interoperable digital identity ecosystem needs both:

- Parties that issue valued credentials — primarily in the public sector, often in forms such as passports, birth certificates and driver’s licences; and

- Trusted parties that can authenticate and vouch for users — such as banks, who undertake Know Your Customer (KYC) reviews.

This combination can empower consumers with choice in how their identity details are protected and passed, protect against fraudsters and scammers, and enable businesses to safely engage in eCommerce.

Identity Matters

Digital identity is the vital entry ticket to participate safely in our increasingly digitalised economy, equipping people for their digital lives and verifying the other end of the internet connection.

It’s an urgent problem. Without secure and expedient alternatives, users gravitate towards the ubiquitous “log in with Facebook” (or similar) to access their digital lives. While convenient, this approach is neither safe or reassuring, with the known scourges of fake profiles and cyber attacks, at a time when Deloitte estimates that fraud annually costs the global economy over US$3.7 trillion.[1]

Some advocate for various models of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), with users attesting their own provenance. User- empowerment is an important principle, but it must combine with reassurance for the counterparty at the other end, if it is to be safe and help to combat identity theft.

Against these challenges, there are opportunities. Where banks’ KYC efforts seek to combat fraud and financial crime, this has already made banks a type of ‘secure identity hub’, underpinned by public sector credentials. Leveraging these capabilities could enable new trusted identity services with user choice, as championed by the Global Assured Identity Network (GAIN).[2]

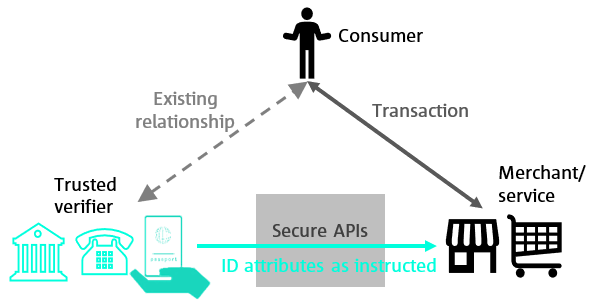

Figure 1: Open Digital Trust model (Source: Institute of International Finance)

Building on existing OpenID Foundation standards for Financial-grade APIs and the Open Digital Trust initiative with the Institute of International Finance, GAIN envisages that consumer (or small business end-user) could instruct one of their existing trusted counterparties (such as a bank or telco or energy retailer) to verify their identity. Significantly, this model would enable the consumer to dictate the specific identity attributes that are passed (see Figure 1).

For in-the-moment identity verification to enable an interaction, this context differs from the nature of the data transfers facilitated by Australia’s Consumer Data Right. But while the mechanics are different, there is a common philosophy: the consumer is always empowered and in control, selecting which of their data attributes are passed, when, to whom, and by the counterparties that they use and trust.

The Public Sector is a Vital Enabler

Public credentials play an important and unparalleled role in the ecosystem, being the most recognised form of identity proof. Passports and driver’s licences (and cards from agencies such as Medicare) form the basis that banks and other entities utilise today in KYC — and efforts to modernise with digital driver’s licences will be crucial for enabling banks to do this better.

There are impressive steps underway, with some Australian states implementing digital driver’s licences, and some even aspiring for their Services apps to provide integration across state government services, like the blockchain-enabled Estonian model. Some will remain uncomfortable with centralised government databases, and this is a major motive for SSI, but for most use cases, it is difficult to envisage genuine trust or confidence in identity provenance that is not underpinned by such credentials.

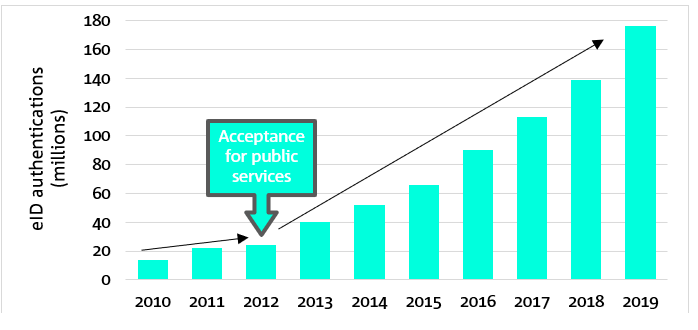

Figure 2: Norway BankID Authentication Usage Trajectory (Source: Vipps International, BankID, Norway).

As well as issuing credentials, public services are amongst the most important uses for digital identity, across taxation records, health, education and more. For any digital identity system to achieve widespread adoption, it is vital to deliver linkages across all walks of life for the end user, including these services. Where the Nordic BankID system has become a world leader in usage, privacy and security, its uptake accelerated once public services were included (see Figure 2).

A key learning from that Nordic case is that public and private sector entities need to co-operate and support each others’ use cases. A system will not achieve maturity or critical mass from isolated approaches and/or efforts to crowd each other out.

The Private Sector Can Help

There is also an important private sector role, bringing benefits and solving problems that the public sector cannot do alone.

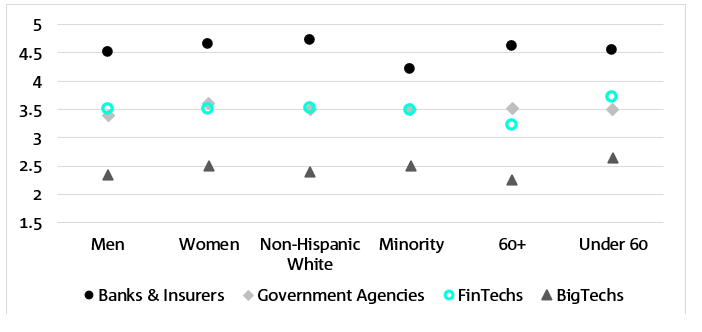

Firstly, for reasons of privacy and data protection, consumers may prefer private sector firms to handle the sensitive data attributes that comprise their ‘identity’, as well as the transactional history of what they buy and who they correspond with. Successive international studies have shown that consumers trust banks with their personal data, more than they trust other parties, including the public sector — and trust is crucial for driving mass adoption. A recent Bank for International Settlements (BIS) report highlighted this preference across all demographic segments (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Consumers’ Data Trust by Counterparty and Demographics (Source: Bank for International Settlements)[3]

Bank authentication can minimise how much of the consumer’s data needs to be passed. Where a business needs to validate that a customer is over 18, they don’t need their passport or drivers licence number, or address, or even their precise age — the consumer can instruct their bank to simply answer the question: “Can you authenticate that this person is 18 or over? Yes or no” — ie. a ‘zero knowledge proof’, where nothing additional is revealed. In this scenario, data minimisation is embedded in the design, and the customer is empowered with complete control over the specific identity attributes that are shared.

Secondly, banks have an important role to play helping counter fraud and scams. An interoperable identity ecosystem could empower consumers to validate the destination account before they transfer money, and overcome the menace of invoice fraud. Against the explosion of phishing and false invoices, consumers and businesses are safer when they can use their bank to validate their counterparties.

Thirdly, banks’ authentication capabilities are not limited to consumers, but also encompass banks’ business customers: registration and office bearers; who is authorised to act for the company; its legitimate banking details for payments.

Fourth, banks can help extend the reach beyond those that have traditional credentials, enabling greater inclusion. As one example, UnionBank of the Philippines has already helped to connect citizens in remote villages to the banking system, and there is potential for similar in Australia’s remote indigenous communities and in the South Pacific islands.

Fifth, identity services need to extend beyond the state and national borders, supporting online transactions, migrants and tourists. Most government identity initiatives around the world have invariably been citizen-centric — in fact, Singapore’s initiatives to link identity and payments systems in pilots with Thailand and India were specifically motivated to address this gap, with recognition that they are a migrant economy. Trusted private sector firms can attest to a user’s home market credentials, across identity, payment details, and the veracity of skilled trade qualifications.

Open Ecosystem, Secure Solution

We need a secure identity ecosystem that doesn’t allow the unfettered anonymity used by criminals, but which respects privacy, is safe, and provides choice.

In an open ecosystem, the private sector authentication opportunity is not limited to banks, with other verifiers also welcome to participate. Banks are arguably the best placed to offer a wider range of verification services, given the role of KYC and the depth of data held, but it is ultimately for customers and suppliers to decide which authenticators they are willing to trust. For some use cases, a lower level of assurance may suffice, and other firms (in telecommunications, or energy retailing, or insurance) may have particular expertise or efficiencies. The OpenID Foundation standards provide a secure basis for an open ecosystem in which all firms are welcome to participate, and this is already happening across the world.

At NAB, we see immense opportunity for how we can help support our business and consumer customers alike, but invariably it is not something we can do alone. It is not enough for us to assure a business or an agency that we can verify the 25% of their own customers that bank with us — to reach a critical mass, we need to partner with not only the public sector, but also other banks and other verifiers, so that we can collectively offer complete and seamless coverage across the community.

Supporting the digital economy can be commercially beneficial for authenticators, in dynamically supporting customers (and not ceding the role to BigTech firms), reducing fraud and operational losses, and potential new revenue streams in services for corporates and new insurance products. But this won’t hold up if the market is fragmented, or if public sector initiatives and regulatory frameworks disincentivise the private sector from investing. Without all parties, many important use cases will be left unsolved.

Towards an Interoperable Identity System

We need an integrated, interoperable ecosystem, utilising the best of public sector credentials and the privacy and security controls of regulated firms, allowing users to direct which parts of their identity credentials are transferred when and to whom. We can make it easy for people to engage via a safe, secure, trusted method, with control and choice of the authenticating party they use.

To achieve this, the public sector (across federal and state levels) and private sector firms (in financial services and beyond) each need to recognise that they have a vital role to play, but also that their part alone is not a panacea. By enabling each other, a robust, trusted and accessible system is within reach.

____________________________

References:

[1] See Deloitte – Elevating the fight against financial crime

[2] See Global Assured Identity Network (GAIN) – White Paper

[3] Bank for International Settlements-Whom do Consumers Trust with their Data? US Survey Evidence

____________________________

The conversation continues at the Future Identity Festival 2022, 14th – 15th November at The Brewery, London.